We Built This

Tell the truth, shame the devil

There are moments in movement work when you don’t realize you’re standing at the edge of something new until years later — when everyone is suddenly speaking a language you remember inventing out of necessity.

We Built This was one of those moments.

Taylor and I didn’t set out to create a “model.” We weren’t chasing innovation grants or thought-leader panels or the kind of attention that only arrives once something has already been sanitized, renamed, and professionalized.

We were trying to solve a very specific problem.

Black people — especially Black millennials — were being talked about constantly in American politics, but almost never spoken to with respect, cultural fluency, or honesty. Our power was assumed. Our turnout was demanded. Our grief was mined. And our actual political education? An afterthought.

So we built something different.

This was before “digital organizing” meant vertical video and meme teams. Before TikTok explainers. Before “narrative strategy” became a line item instead of a survival skill.

We Built This lived at the intersection of culture, clarity, and accountability. It treated Black millennials not as a turnout problem to be solved, but as people with history, taste, humor, rage, skepticism, and receipts.

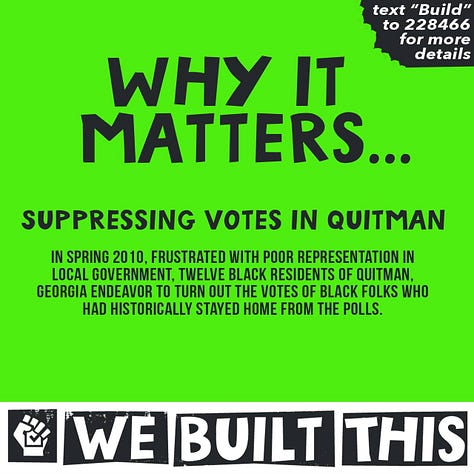

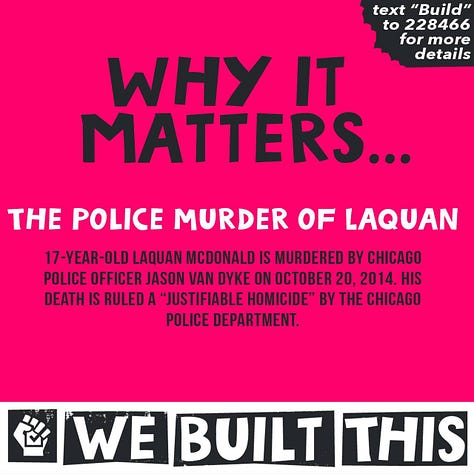

We used pop culture, music, Black internet language, plainspoken political education, down-ballot obsession, and storytelling rooted in lived experience. Not because it was cute — though it was — but because it was true.

We didn’t flatten politics into slogans. We contextualized it. We explained how systems actually worked, why local races mattered, and why voting alone was never the point — but still mattered. We talked about power without condescension. We assumed intelligence. We respected doubt.

And we did it without asking permission.

How it started

We Built This emerged at a moment when Black millennials were being treated as both politically essential and strategically disposable. We were expected to save elections but not trusted with strategy. Courted for turnout but ignored on narrative. Talked at, not talked with.

The room where it was created was small on purpose. At first, it was just Taylor and me.

Institutions like to call what we were given “free rein.” But it wasn’t trust — it was distance. No one was paying close enough attention to imagine what we might build. There was no script, no playbook, no committee hovering with edits. Just enough space to tell the truth as we understood it.

We came at the work from opposite ends of the millennial spectrum — me from the tippity top, Taylor from the tippity bottom. Different reference points. Different political entry points. Different relationships to the internet, to institutions, to hope.

That full arc of the generation turned out to be the secret sauce.

When I instinctively wanted to lead with long explainers — structure, history, stakes — Taylor pushed us to sharpen the language and meet people where they already were online. When Taylor wanted to move fast on tone or humor native to younger millennials, I slowed us down just enough to make sure the politics underneath were solid and durable.

If something landed for me but not for Taylor, it wasn’t done. If something felt urgent to Taylor but didn’t make sense to me, we kept working.

That tension became the work’s integrity.

So we did something simple and radical: we spoke to our people like adults.

We focused on down-ballot races. On local power. On issues that actually touched people’s lives. We used culture not as decoration, but as infrastructure — music, language, art, humor, shared reference points.

We weren’t trying to go viral.

We were trying to make politics legible, grounded, and worth engaging.

And it worked.

Why it had to exist

What often gets lost in the retelling is that We Built This didn’t emerge in a vacuum. It came out of a broader ecosystem of Black organizers, artists, and political educators experimenting in real time — often without funding, permission, or protection.

Right before We Built This, I came out of institutional political work at Color of Change that quietly gutted me.

My ideas were taken. My labor was absorbed. The work moved forward; my name did not. I was made to believe — subtly, professionally, efficiently — that while the work was good, I was not the reason for it.

That kind of harm doesn’t show up as chaos. It shows up as discipline. As process. As being told you’re “not ready yet” while watching your ideas travel without you.

By the time I left, my self-esteem was in the basement.

What I didn’t lose — even then — was my political clarity.

I knew what wasn’t working. I knew how Black voters were being mishandled — mobilized instead of respected, flattened instead of engaged. I knew we didn’t need another clever frame or last-minute panic. We needed political honesty. Language that assumed intelligence. Structures that treated people as full political actors.

We Built This wasn’t just a creative project. It was a refusal.

Then Trump won

Trump’s first presidency wasn’t just a political crisis — it was a narrative one.

Disinformation was everywhere. Nihilism was fashionable. Exhaustion was constant. And Black organizers, especially young ones, were expected to hold the line without tools, visibility, or real support.

So We Built This evolved.

The second iteration — this time co-created with Blessitt — expanded from a campaign into a platform. We deepened the political education and introduced a podcast — not as content for content’s sake, but as infrastructure.

The podcast did something quietly radical at the time: it put young Black organizers, strategists, and thinkers on the mic — not as sidebars or inspirational quotes, but as full political subjects with analysis, critique, and vision.

We weren’t just explaining what was happening.

We were training people how to think through power in real time.

We talked about organizing under authoritarian conditions. About local resistance when national politics felt broken. About what Trumpism actually was — and what it wasn’t. About why despair was understandable but not useful. About how movements survive long winters.

And in doing that, we helped put a generation of Black organizers on the map — people who are now running campaigns, leading organizations, shaping narratives, and building power in their own right.

That part doesn’t get said enough.

Legacy, amnesia, and now

A lot of what people now describe as “best practices” for Black digital organizing came after We Built This:

Culture-first political education.

Meeting people where they are without dumbing things down.

Treating Black voters as political actors, not demographic abstractions.

Using art, humor, and narrative as organizing tools — not window dressing.

Building platforms that double as leadership pipelines.

That wasn’t accidental.

But legacy is tricky. The most influential work often gets absorbed, rebranded, and detached from its originators. You see the tactics everywhere now. You hear the language. You recognize the tone.

And every election cycle, the same amnesia sets in.

Suddenly, everyone is shocked that young people are politically sophisticated. That they understand down-ballot races. That they respond to narrative, culture, humor, anger, and love — not just fear and scolding.

Every four years, a new crop of consultants acts like they discovered fire.

But some of us remember.

Because we were there.

Why it matters now

Black millennials are no longer the “young people” in the room.

We’re organizing now with political memory. With scar tissue. With bodies that have lived through recession, surveillance, burnout, police uprisings, pandemics, and two Trump presidencies.

At the same time, we’re organizing alongside Gen Z — a generation that didn’t inherit hope and slowly lose it, but came of age inside collapse.

The work now isn’t for one generation to instruct the other.

It’s for us to compare notes across time and build something sturdier than what either of us was handed.

We Built This matters now not because it was first, but because it understood something early: movements survive when people are treated as full political actors — not demographics to be managed, not hope to be projected onto, not labor to be extracted.

It took me years to understand the personal cost of erasure. Years to trust my own voice again.

By the time I was invited to name this work out loud by the brilliant Jessica Byrd at Black Camp, I realized something simple and necessary: not telling this story wasn’t humility. It was erasure.

And movements don’t survive erasure. They survive lineage. Records. People willing to say: this is where it came from.

So let me say it plainly, for the record and without apology: I was there at the beginning. I helped build the blueprint.

If the work feels familiar now, it’s because you’re standing inside something we made.

Which is the point.

We built this for us.

Absolutely you and Taylor (don’t know his last name???) Built This political movement. I’m so very proud of your leadership and dedication and commitment to our community. This should not go unnoticed or unrecognized. Let’s make this article go viral. I’m sending to all of the Substack community I follow. I hope this becomes a trend and y’all get the proper support and recognition deserved. Thank you again Aimee Castenell for another brilliant piece 👏👏👏👏👏🤯🤯🤯🤯